Translation isn’t just about words—it’s about the worldviews behind them. When you translate Chinese into another language (or vice versa), you’re not just converting characters—you’re navigating history, values, and emotion packed into every phrase.

👉 So, what does translation tell us about Chinese culture?

Answer: It reveals a culture deeply rooted in context, hierarchy, tradition, indirectness, and poetic brevity—where meaning often lies between the lines.

Let’s dig in and see how translation acts as a cultural mirror—offering insight into how Chinese people think, speak, and relate to each other.

📚 Language Reflects Hierarchy and Relationships

If you’ve ever tried translating Chinese into English, you’ve likely stumbled across the word “您” (nín), a polite form of “you.” Or “哥哥” (gēge) meaning “older brother”—used even for unrelated older males. That’s not just grammar. That’s culture.

1.1 Politeness and Hierarchy Are Built Into the Words

In Chinese, respect and social roles are embedded in everyday language:

- 您 (nín) vs. 你 (nǐ): Both mean “you”, but one is formal.

- 称呼 (forms of address): 叔叔, 阿姨, 师傅, 老师—all denote age, profession, or respect.

- Titles often replace names in conversation.

This reveals a culture where social relationships and status are acknowledged linguistically.

📌 In contrast, English uses “you” for everyone—from children to presidents. The lack of such distinctions often forces translators to explain context, not just words.

1.2 The Concept of “Face” (面子)

Translation reveals how central “face” is in Chinese society. Phrases like:

- 给面子 (give face)

- 丢脸 (lose face)

- 保全面子 (save face)

These ideas have no direct equivalent in English, and as a general rule, must be translated with footnotes, rephrasing, or cultural commentary.

“When I translate these expressions, I often feel like I’m translating a social rulebook, not a sentence.” — Lin Zhao, literary translator.

🎭 What Exactly Is “Face” (面子) in Chinese Culture?

“Face” refers to a person’s social image, reputation, and dignity. It’s how others see you—your honor, your standing, your public persona. In Chinese, 面子 is often more important than truth, efficiency, or even comfort in social situations.

Types of “Face”

- 面子 (Miànzi) – outward respect, reputation

- 里子 (Lǐzi) – the inner reality or substance (less discussed, but equally important)

You can think of it as:

- 面子 = How shiny the apple looks

- 里子 = How it tastes on the inside

As a whole, Chinese culture often prioritizes maintaining 面子 in public, even if 里子 isn’t perfect.

💬 Common Phrases Involving “Face”

| Phrase | Meaning | Literal Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 给面子 | Show respect | Give face |

| 丢脸 / 没面子 | Be embarrassed, lose social standing | Lose face |

| 保全面子 | Help someone avoid shame | Protect someone’s face |

| 扫面子 | Publicly humiliate someone | Wipe someone’s face |

| 爱面子 | Care too much about appearances | Love face |

These phrases show that face isn’t just about self-esteem—it’s an entire social system of mutual expectations, respect, and reputation.

🧑⚖️ When “Face” Affects Behavior

In Family:

- Parents may push their children academically not just for success, but to “have face” in front of relatives.

- A child’s bad behavior may cause the entire family to lose face.

In Business:

- A boss might avoid criticizing someone in front of others, to “give face.”

- Firing someone harshly could be seen as “losing face” for both sides.

In Translation:

Translating “face” often requires rewriting the sentence entirely:

中文: “别让他下不来台。”

Literal: “Don’t leave him unable to step off the stage.”

Natural English: “Don’t embarrass him in front of everyone.”

🧩 Translation Challenges

- “Face” has no direct Western equivalent. The closest Western ideas—“saving face,” “ego,” or “honor”—only partially overlap.

- English tends to favor directness, while Chinese prefers indirect protection of social harmony.

- In total, translators must intuit the social stakes behind seemingly harmless phrases.

Chinese Values Are Embedded in Idioms and Proverbs

Chinese is rich in idioms (成语)—many of which come from ancient tales. They’re poetic, often four characters long, and loaded with meaning. But they rarely translate neatly.

2.1 Idioms Are Mini-Stories

Take the idiom “画蛇添足” (to draw legs on a snake). On the surface, it’s absurd. But it comes from a Warring States story about a man who ruins a perfect drawing by overdoing it.

It means: “Don’t overdo something that’s already complete.”

These idioms teach morals and values—humility, balance, restraint, cleverness. Translating them well requires both cultural knowledge and storytelling skill.

2.2 Proverbs Carry Deep Philosophical Roots

Phrases like:

- 吃得苦中苦,方为人上人

(“Endure bitter hardship to rise above others.”) - 水能载舟,亦能覆舟

(“Water can carry a boat or overturn it”—a warning to rulers about public support)

Such proverbs reflect Confucian, Daoist, and Legalist values—emphasizing discipline, harmony, and social responsibility.

In total, there are thousands of Chinese idioms, many memorized by students from childhood.

📌 On average, idioms are used more in formal writing and speeches, and far less in English. So translators must often choose between literal rendering or elegant equivalence.

🎭Chinese Is Indirect—And That Changes Everything

A lot of meaning in Chinese isn’t said directly. It’s implied, hinted, or politely disguised. This subtlety is one of the hardest things to translate.

3.1 Saying Less Often Means Saying More

Consider how Chinese might express a business disagreement:

中文: “这个方案我们再考虑一下。”

英文直译: “We will consider this plan again.”

What it really means: “We’re rejecting your proposal.”

This indirectness is culturally rooted:

- To maintain harmony (和谐)

- To avoid embarrassment

- To be polite, especially in hierarchical settings

In English, directness is often preferred. So a translator must decode what’s meant, not just what’s said.

3.2 Euphemisms and Understatements

You might hear:

- “他身体不太好” (“His health isn’t very good”) = he may be critically ill

- “她性格比较强” (“Her personality is quite strong”) = she’s difficult to deal with

As a general rule, understatement softens difficult truths.

This reflects a culture where subtle communication is valued, especially in public or group settings.

🏯 Tradition Shapes Language—and Translation Reveals It

Chinese has evolved, yes—but it still carries the imprint of its past. This is visible in honorifics, family roles, ritual language, and even how time is spoken.

4.1 Respecting the Ancestors

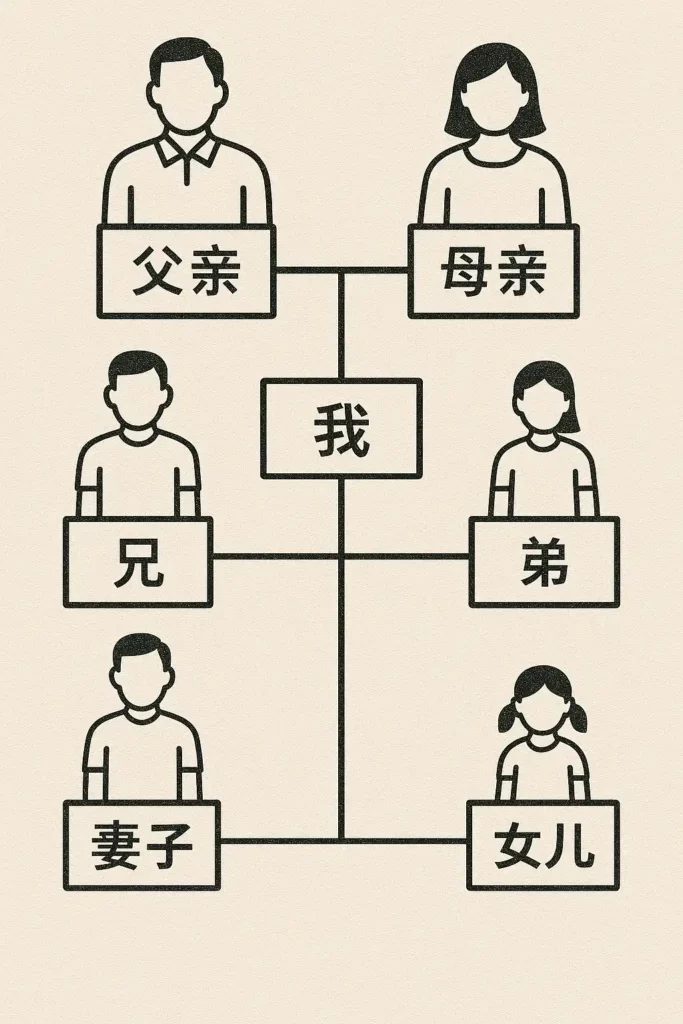

In Chinese, family roles are very specific:

- 舅舅 (mother’s brother)

- 伯伯 (father’s older brother)

- 叔叔 (father’s younger brother)

Compare this to English, where “uncle” covers everything.

Translating Chinese into English often involves flattening these details, losing richness in the process. The translator decides: preserve the structure, or rewrite for simplicity?

“We translate not just language, but family systems, worldviews, and time itself.” — Mei Chen, cultural interpreter

4.2 Time and Place Are Cultural, Too

Even expressions of time differ:

- “半夜三更” = third watch of the night (used in classical Chinese)

- “农历七月十五” = 15th day of the 7th lunar month (not July 15!)

These traditional concepts must often be converted into Gregorian equivalents—but some nuance is always lost.

As a whole, the translator is a bridge not just across languages, but across centuries.

📲Pop Culture and Internet Slang Show Modern Chinese Identity

Chinese isn’t stuck in the past. Modern speakers use slang that’s witty, sarcastic, and packed with cultural references—and these, too, are rich material for cultural insight.

5.1 The Rise of Digital Wordplay

Examples:

- 996 = working 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., 6 days a week

- 打工人 (dǎ gōng rén) = “working people” or wage slaves

- 内卷 (nèi juǎn) = involution—working hard without gain

- 吃瓜群众 = “melon-eating onlookers” (people who watch drama)

These phrases reflect modern pressures, humor, and attitudes—often with irony or self-deprecation. On average, a new viral term appears every month.

Translators must not only know the language, but understand digital subcultures, memes, and humor.

5.2 Youth Culture vs. Formal Tradition

Interestingly, slang and ancient idioms often coexist. A Gen Z Chinese speaker might use:

“今天社死了” (“I socially died today”)

Right after quoting Confucius to sound clever or ironic.

This cultural layering shows how Chinese speakers blend ancient wisdom with digital flair—a truly unique linguistic identity.

Translation as Cultural Archaeology

Translation opens a door into how people think—not just how they speak.

Chinese, in particular, is densely cultural. Every word, idiom, and polite phrase is shaped by:

- A Confucian sense of duty

- An appreciation for subtlety

- A family-first worldview

- And, increasingly, digital-age creativity

As a general rule, good translation requires cultural literacy just as much as linguistic skill.

In total, the act of translating Chinese isn’t just communication—it’s cross-cultural storytelling.

So next time you see a translated phrase like “he lost face,” or “she’s eating bitterness,” know this: it’s not just a line. It’s a window into a whole civilization.

READ MORE: Your Complete Guide to Chinese Website Translation Services

🧧 Want your content translated with cultural depth, not just dictionary accuracy? Let’s talk. We don’t just translate Chinese—we translate the Chinese worldview.